Power Meters and Ultra Endurance Racing

Posted by Kurt Refsnider on June 1, 2022

In the world of ultra endurance racing (defined here as any effort that stretches through an entire day or beyond), power meter use is far less widespread than in shorter events. But from the perspective of a long-time ultra racer and coach, I’d argue that power numbers can play just as important a role in ultras, whether that’s in the training, for pacing, and for exercising restraint in the opening hours of a long race. Here I’ll share a bit more about each of those topics, so read on - I think there’ll be a few nuggets of insight for fellow ultra racers, the many folks out there curious about perhaps trying an ultra-distance event, as well as for many folks who stick to single-day events, too!

Training for ultras with power - it’s not all just long, easy efforts

The reality of ultra endurance events is that “race pace” is pretty dang slow in the grand scheme of things, and similarly, power output is relatively low. One simply can’t push really hard, or even moderately hard in many cases, for 15 or 24 or 48 hours or more. As a result, it’s not uncommon that riders train for such events with huge volume at relatively low intensities. I did that myself years ago, riding 1,000+ hours a couple different years without too much intensity at all. Sure, I could ride forever, but I didn’t have much speed. When I began increasing the amount of training I did in zones 3 and 4 and even above FTP and dropped the number of hours I was riding by 25+%, I got considerably faster in 2+ day efforts. It was at that time that I started training with a power meter to better gauge my various training efforts. Just what the workouts and progression look like depends so much on the target event, one’s athletic background, time available for training, etc.

Power also is a far more reliable measure of effort when training on particularly fatigued muscles when overreaching in big training blocks - heart rate tends to become depressed a bit when overreaching, and RPE increases. So especially for the final few days of a training block and for training binges with a week of 35+ hours, pacing efforts with power can allow one to get far more out of the time in the saddle.

Pacing off heart rate can be unwise for long efforts

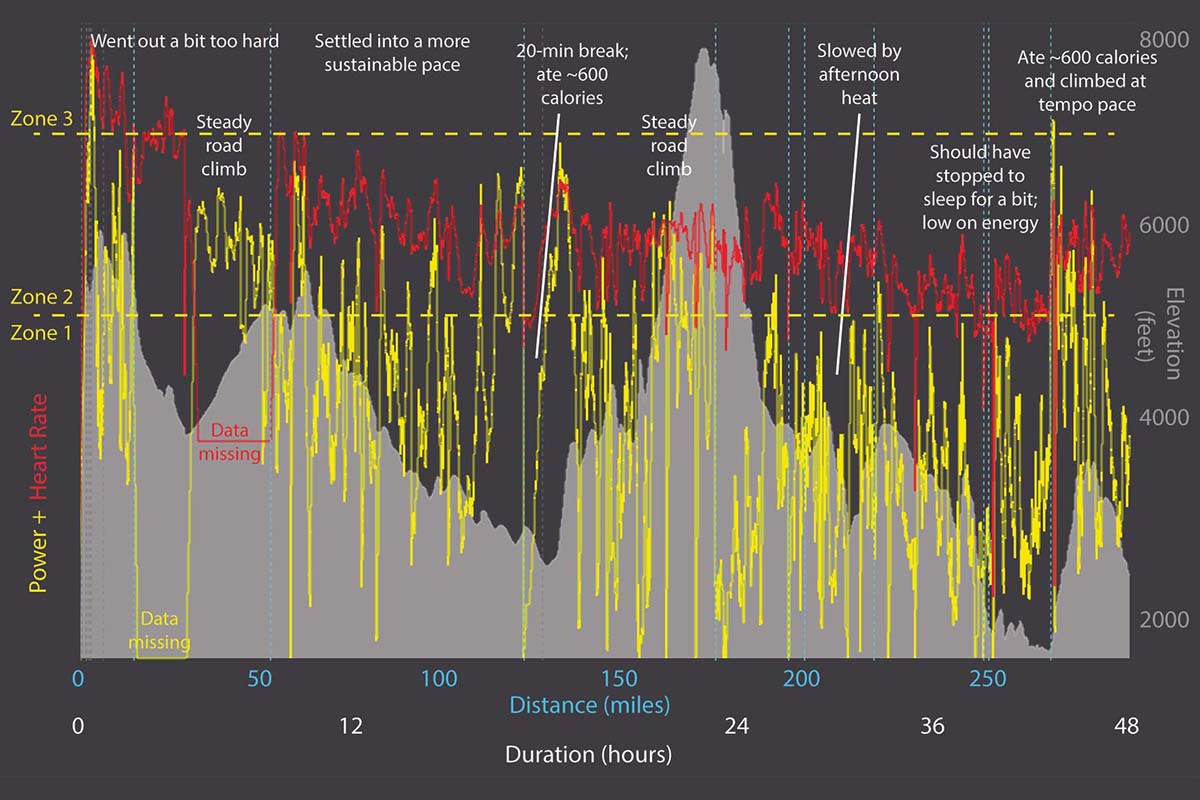

In long efforts that stretch beyond 8 or 10 hours, heart rate and power output typically become decoupled, a phenomenon known as cardiovascular drift (or more specifically in this scenario, reverse cardiovascular drift). With a steady power output or RPE, heart rate will gradually decline during loooong efforts. A variety of factors are likely responsible for this (e.g., caloric intake, hydration status, an increase in efficiency of oxygen and energy transport), and it remains an active area of study. But what does this mean for endurance athletes? If pacing off heart rate, it will take a higher power output and result in a higher RPE to maintain a steady heart rate as a long event wears on. Thus, heart rate can be quite deceptive for long efforts, and pacing off power and/or RPE is far preferable.

Use power as a governor early in long efforts

The start of any long race (and short races, too!) is the culmination of so much preparation - the training, the mental prep, the gear, the nutrition plan, route research, strategy, and more. At the start line, excitement is high, most everyone is stoked (and likely a bit nervous), tapered, feeling fresh, and antsy to go! As soon as the race begins, folks at the front are hammering, far harder than they probably should be for such a long race. But between the excitement, feeling fresher than they have in weeks or months, and that competitive thrill, they’re likely digging even deeper than they realize they are. None of them are going to win such a long race in the first few hours, but they sure could lose it by digging themselves into a hole. It’s all too common to see numerous riders crumpled in the shade along a trail the first afternoon of a multi-day race, battling cramps from having gone out far too hard.

So how can a power meter help? I use power numbers to set a governor for myself on the first day of an ultra (or it could be the first few hours of a 100-miler, the first few laps of a 24, etc.). For something like the Arizona Trail 300 (see the power/heart rate plot), a rugged singletrack effort that might take me 45 hours, my goal would be to keep my power under mid zone 3 and mostly in mid zone 2 on all but the steepest of the short climbs early in the route. And on those steep climbs, if my power gets up to around my FTP, I’ll get off and walk. The mission is to not dig a hole at all in those first hours. This strategy has worked so well for me; far too many times, I’d sabotaged myself a bit by going out way too hard and paying for it with some very sluggish muscles between hours 6 and 8. By the first evening, I’ll start to focus on simply keeping my power somewhere in zone 2 most of the time when pedalling; if I’m feeling descent, that’s a reasonable pace for hours and hours and hours. By 24 hours in, I usually begin to ignore my power numbers and simply ride by feel, but I’ll keep collecting the power data for analysis after the event. There’s so much to be learned from dissecting data from big efforts, and they can provide so much valuable guidance in getting to the start line of a long event and in pacing wisely for that effort!

About Kurt Refsnider

Kurt Refsnider, Ph.D. rides on the Industry Nine - Pivot Pro Backcountry Team and has been racing ultra-endurance mountain bike events since 2008. He’s won and/or set records in everything from Tour Divide to the Arizona Trail 300 and 750 to the Colorado Trail Race to Alaska’s Iditarod Trail Invitational. His passion is riding in remote landscapes and on rugged backcountry trails. Kurt is also a cycling coach at Ultra MTB and a co-founder and Routes Director at the Bikepacking Roots non-profit.